Taking the road less traveled became my creed—from the Pacific northwest to the Caribbean—and I’ve lived life wide open. These are pieces of the journey: the places, the people, and the quiet truths found between the storms.

Discover Jim Buresch

Jim was born in Pittsburgh, PA but raised in the Appalachian Mountains in West Virginia by his grandparents, the Reverend Clarence and Mary Ethel Fortner. His story began in a small house in Leatherwood, WV, where he lived with three uncles, two of his four aunts, and a potbelly stove for heat. There was no bathroom—just an outhouse for the family of eight.

Like his grandfather, Jim had an early passion for politics and public service. As a teenager, he was elected national president of the Teenage Republicans and, by 18, served on the Mingo County Republican Executive Committee in the southern coalfields near the Kentucky border.

Early Years and Education

His educational path started at West Virginia University but took a turn when he enlisted in the U.S. Army, realizing he wasn’t quite ready for college life. When he returned to academia, it was with renewed focus. At Marshall University, his leadership stood out—he was elected student representative to the Board of Governors and served as Student Body Vice President.

During his junior year, Jim began volunteering with the Huntington AIDS Task Force alongside two other students. He started by transporting leftover medications from deceased PWAs (People With AIDS) to those still fighting to survive. He spent countless hours on the phone with men who had once thrived in big cities but returned to small, closed-minded towns to die—alone.

Just a few years earlier, Oprah Winfrey had come to Mingo County to cover the story of a public pool being shut down because a man with HIV had swum in it. That’s the climate Jim worked in. But he wasn’t deterred.

When he wasn’t delivering meds or supporting clients, he was out educating—speaking in schools, churches, and civic organizations about HIV. When the Task Forces’ director stepped down, they turn to Jim. At the same time, he envisioned a takeoff of the Gay and Lesbian rights organization, Human Rights Campaign in DC and started, alongside allies like Larry Barnhill, Okey Napier and school board member Julia Hagen, the Huntington Campaign for Human Rights.

As director, one of Jim’s biggest challenges was fundraising. He organized several campaigns, but none more memorable than Illusions of the Stars, a drag queen revue he produced in 1992. He convinced the Mayor and the City of Huntington to allow the show to be held in the City Hall auditorium—not once, but two years in a row. In West Virginia. That bold success laid the groundwork for his campaign to push the city council to pass protections for gay and lesbian citizens in housing and employment.

Queer Nation and Outing

But Huntington wasn’t ready.

When the city council voted down the proposed protections for gay and lesbian citizens, the backlash was loud—and creative. Suddenly, thousands of fake $3 bills flooded downtown, each one bearing the face of a councilman and claiming he was “as gay as a three-dollar bill.” Queer Nation of Columbus, Ohio, took responsibility for the stunt. But in the court of small-town public opinion, the blame fell squarely on Jim Buresch.

The local newspaper fanned the flames, pointing fingers, and the whispers got louder. Jim had stepped into the spotlight—and now he was feeling the heat

Gays in the Military

In 1992, during the historic LGBT March on Washington, Jim was invited to join a group of former service members who had been discharged for being gay. Their mission: to help repeal the military’s ban. Organized by the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force, the group—dubbed the “Alpha Squad” by Tom Swann—was led by Colonel Margarethe Cammermeyer.

Their lobbying target: Senate Majority Leader Robert C. Byrd of West Virginia.

During a meeting with Byrd’s Chief of Staff, Jim was given the floor. He didn’t hold back.

“Is Senator Byrd ready to give up his KKK hood and robe and support gays serving openly in the military?”

The meeting ended immediately and Cammermeyer shot Jim a look of death. “There was no way a known Klansman would support gay anything, they were delusional,” Jim recalled. It would be nearly 20 years later that Sen. Byrd would vote as an Arms Services committeeman to allow the repeal of Don’t Ask Don’t Tell.

But Jim didn’t regret it. He believed in speaking truth to power—and still does. Even if it got him blackballed by some LGBT leaders in D.C., he considered it a victory of conscience.

Back home in West Virginia, the cost of that conscience got steeper. The death threats that had started a year earlier were getting more serious —so serious that the local police got the West Virginia State Police involved. Threats were traced from across the state. “I called my family for help, one of my uncles took the phone and said I was getting what I deserved,” he’s recalled. “Why did you have to go and tell the whole world,” his Uncle said to him referring to Jim’s coming out of the closet on WSAZ’s 6:00 news, the local NBC affiliate, in 1991, in deeply religious West Virginia.

People leaving The Driftwood Lounge, a local gay bar, were attacked. His actions were causing others to be harmed, and he felt that responsibility deeply. Jim and a friend were jumped one night; a crowbar and broken beer bottle the weapons used against them; his friend was hospitalized with permanent injuries.

In the midst of all this, Jim was reading The Mayor of Castro Street, the biography of Harvey Milk. When he reached Milk’s famous “boy from Altoona” speech, something clicked.

It was time to head west.

California: A New Beginning

“California, open up your golden arms—here I come.” – Sophie B. Hawkins

At 23, Jim arrived in San Francisco with nothing but a suitcase, a stubborn spirit, and the dream of finding a place that fit. The Castro welcomed him with open arms and tight jeans. He landed a job at Wild Wild West, a gay and lesbian country-western apparel shop in the heart of the district, owned by Mike Smith (also known as Murray Selkow), a founding member of the original radical group, Gay Liberation Front—and the inventor of Randy’s Rolling Papers.

One afternoon, a straight woman wandered into the store looking for boots. Her boss was attending the christening of the new Joshua Tree National Park.

“Who’s your boss?” Jim asked.

“Senator Feinstein,” she replied, gathering bags of boots.

As she walked out, Jim barely held back the urge to shout, “Tell Senator Byrd I said hello!”

A few months later, in a smoky underground SOMA bar called The Pitt, Jim met Alain—a soft-spoken Frenchman with limited English and wide, curious eyes. Their connection was instant. They explored the Bay Area like two teenagers in a lucid dream—tripping on acid, wandering through Land’s End, and falling more in love with each other every step of the way.

Jim was living the fairy tale he had once dared to imagine from a porch swing in West Virginia.

A Life-Changing Diagnosis and a Return to Activism

In 1994, the dream cracked. At age 24, Jim got the news that changed everything.

“I found out on April 1st—April Fool’s Day,” he says. “I asked Dr. Sophia Chang at UCSF if it was a joke. But the look on her face told me I was going to die—just like thousands of others.”

HIV. It hit like a freight train.

Alain, who worked at a Castro laundromat, began introducing Jim to a different kind of San Francisco royalty—men like Scott Miller (Harvey Milk’s former lover), Gilbert Baker (creator of the rainbow flag), Cleve Jones (creator of the AIDS Quilt) and Dennis Peron (the godfather of medical marijuana and as the newspaper called him, “King of Pot”).

Dennis became more than a mentor—he was a father figure. A north star. Just like Jim’s grandfather had been.

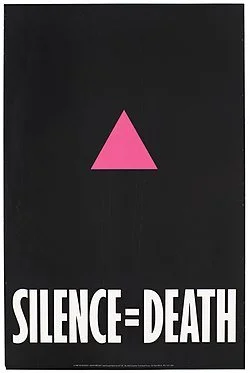

ACT UP San Francisco

Later in 1994, Jim walked into his first ACT UP San Francisco meeting. It was loud, electric, radical—the city’s most visible and controversial direct-action group fighting for people with AIDS. Dennis Peron had warned him: “Don’t get too involved. I’ve seen too many burn out.” But Jim was angry, scared, and had nowhere else to put all that energy.

He dove in headfirst.

In 1995, he joined other activists in storming the Republican Party’s San Francisco headquarters. They climbed the building’s balcony overlooking Van Ness Avenue. Jim set an effigy of California Governor Pete Wilson on fire. Others torched likenesses of Reagan and Bush. It was raw, defiant street theater.

The police came fast. Jim took off up Van Ness and ducked into The Iron Horse, one of San Francisco’s original gay bars. Without missing a beat, the bartender pointed to the beer keg well under the bar. Jim climbed in. When the cops burst in asking where the arsonist had gone, the entire bar played dumb.

They searched. Found nothing. Left.

Jim had escaped—thanks to a bartender, a bar full of solidarity, and a hidden space beneath the beer.

That night, something inside him shifted. There was no going back.

He became a fixture in the movement. He marched, chanted, die-in’d, kiss-in’d, shut down traffic to the Bay Bridge, and raised hell with purpose. At the 1997 Castro Street Fair, he and Alain unfurled a massive pink triangle down the side of an apartment building overlooking the Castro—a bright, screaming reminder of queer history and survival.

But ACT UP was starting to fracture. A faction had embraced the Duesberg Theory—the dangerous claim that HIV wasn’t a real virus, but a result of lifestyle and medication. For Jim, who had seen too many die, who was living proof of HIV’s reality, that was the line. He left the group for good.

Meanwhile, just around the corner from the apartment he shared with Alain, a different revolution was blooming inside a purple Victorian house.

It was Dennis Peron’s place.

“Dennis’ house,” Jim remembers, “was like the home we all wished we’d grown up in—full of love, acceptance, and people who got it.”

It was also the birthplace of the world’s first medical marijuana dispensary: The Cannabis Buyers Club. Within a year, Dennis opened a public-facing club on Church Street. If you had a note from a doctor, you could walk in and find relief. After Proposition 215 passed—the first law in the world to legalize medical cannabis—the club moved to a five-story building on Market Street, near City Hall.

Dennis believed no one should suffer when a natural remedy could ease their pain. And Jim was there, helping build it from the ground up.

One of his most vivid memories is running cheap Mexican weed up from the tunnels of Nogales, Arizona, back to San Francisco. “It was full of fear and determination,” he says. That weed was given—often for free—to people with HIV, cancer, MS, glaucoma, and other conditions.

The club, decorated by Gilbert Baker like a bohemian temple, had layers of rugs, soft lighting, couches, and big trays of cannabis ready for the taking. “It should’ve been heartbreaking,” Jim says. “But the love, the hope, the togetherness—you could feel it. It was thick in the air. It lifted you up.” Eventually, Jim took on a voluntary security role at the club when he wasn’t working in Mountain View—making sure everyone felt safe and cared for. It wasn’t just a dispensary; it was a sanctuary. A living, breathing resistance.

Honoring Harvey Milk: Renaming Market Street

Fresh off the pink triangle installation’s buzz in 1997, Jim launched a bold new campaign: to rename San Francisco’s iconic Market Street to Harvey Milk Street. He believed Milk’s legacy shouldn’t be confined to the Castro—it deserved the city’s main artery. He gathered over 2,000 signatures. Momentum was building. Then the phone calls came.

First, the Castro Merchants Association voiced concerns. Then Supervisor Tom Ammiano called. He had known Harvey personally and said, flatly, “Harvey wouldn’t have supported this.” Finally, a call came from Supervisor Gavin Newsom. He acknowledged Jim’s passion, praised the effort—but asked for a pause. The city had just been through a bruising fight over renaming Army Street to Cesar Chavez Street. “San Francisco needs time to heal,” Newsom said. He promised future support if Jim backed down for now.

Out of respect—and a belief in choosing battles—Jim agreed. He withdrew the initiative. But the fight to honor Harvey’s legacy never truly left him.

Palm Springs & Three Degrees from Cher

As the dot-com boom sent San Francisco’s housing prices into orbit, Jim bought a home in Palm Springs and relocated to the desert. The sun was hot, but the community—though smaller—was fierce and resilient.

Jim jumped in headfirst. He was elected Vice President of both the Stonewall Democrats Club and the mainstream Democrats of the Desert. He advised local legislative candidates and served as volunteer coordinator for a congressional campaign—one aiming to take down Cher’s ex-husband Sonny Bono’s widow, Mary.

“Three degrees from Cher,” he laughed. “I’ll take it.”

2012: “We Won!!!”

In 2011, Jim was tapped to serve as a community organizer in Seattle—his old activist fire rekindled. Washington State was taking on two monumental, citizen-driven campaigns: legalizing recreational marijuana and legalizing same-sex marriage.

Jim worked both.

On election night, 2012, both initiatives passed.

“After years of being on the losing side in our country’s cultural wars, it was beyond excitement when we won, it was soul nourishing,” he said.

Then his phone rang. It was Governor-elect Jay Inslee, calling to personally thank him for his work.

Jim stared at the phone afterward, stunned, the room around him buzzing with celebration. All those years of protest, loss, survival, and persistence had somehow led to this moment. Victory. Jim is pictured here with US Senator Patty Murray (D-WA).

Journalism and Advocacy

In South Florida, Jim pivoted back to his roots—storytelling. He became a journalist for the Independent Gay News of South Florida, covering the pulse of a growing LGBTQ+ community in Fort Lauderdale. He would go on to write investigative stories that resulted in an AIDS non-profit being shut down for corruption and some folks went to prison. Later he would go on to write an investigative piece on the conundrum of gay owned businesses proliferating and profiting from the community’s rampant drug addiction and subsequent rise in deadly STDs. Numerous businesses were forced to change their habits, and two well-known nightclubs were shuttered after the story broke implicating them in ongoing drug activity. “Once again I found myself speaking truth to power and once again I was blackballed, vilified and hated within my community for what I still believe was the right thing to do",” Jim recalls.

It was full circle—his college major, now wielded like a blade and a bomb. His writing wasn’t just reporting; it was advocacy. Each piece he published carried echoes of his days with ACT UP, the Cannabis Club, the Desert Democrats. He wasn’t just documenting the movement—he was the movement.

Professional Journey

Silicon Valley and Banking

A few months after Jim and Alain moved in together, he said goodbye to lazy Castro days in retail. He picked up a temp job—just something to pay the bills. Instead, it cracked open the next revolution.

Jim found himself at Netscape Communications in 1994—ground zero for the birth of the modern internet. It was all floppy disks, dial-up tones, and world-changing ideas. He was in.

From there, he was recruited by Wells Fargo, rising quickly through the ranks to become a Senior IT Project Manager just as interstate banking laws were being swept away. He eventually led the team that went on to certify the bank’s network as Y2K compliant—the moment the world held its breath, waiting to see if civilization would collapse at midnight.

Later, he joined U.S. Bancorp, chasing new opportunities further north. But the cold, gray skies of the Pacific Northwest eventually wore him down. He missed the sun—and something more.

Personal Challenges and Triumphs

Eventually, the weight of Jim’s past came calling. Like many Americans, his life was touched by addiction. But for Jim, the story is more than that.

“I’ve been clean since 2008, sober since 2011,” he says. “But the bad decisions? They started long before the drugs.”

He doesn’t flinch from the truth. “I broke the law to feed my addiction. I paid the price. But hitting bottom—that wasn’t the end. That was the beginning of something real.”

He checked himself into a nine-month recovery home for gay men. He stayed. He worked. He healed.

“I took responsibility for my life,” he says. “And over time, I found my way back—sober, clear, and free.”

But recovery doesn’t wipe the slate clean. “People don’t always let others move on,” he adds. “There’s so much hate in the world now. People enjoy watching each other bleed.”

Then, after a long pause:

“One of my biggest regrets is how my addiction damaged my friendships with Gilbert Baker and Cleve Jones—and how deeply it hurt them, like so many others I hurt with my addiction behavior”

A Return to Art as Activism: Rock it RED! St. Pete

Jim’s activism never really left him—it just changed mediums.

With the backing of Bank of America, the United Nations Association, the St. Petersburg Arts Alliance, LGBT Welcome Center, and local businesses. Jim launched Rock it RED!—a massive public art installation designed to wake people up.

“We wrapped red fabric around every tree lining Central Drive,” Jim says. “It stretched a mile and a half through the heart of St. Petersburg. As you walked or drove down the street, all you saw was red. One unbroken ribbon of remembrance.”

It was a visceral reminder that HIV was still here, still killing, still being ignored. It honored the dead. It called out the silence. And it did what great public art is meant to do—it couldn’t be ignored.

“It was beautiful,” Jim says. “And it meant something.”

Real Estate and Current Endeavors

For more than two decades, Jim has called Florida home, carving out a new chapter in real estate. He became a top-producing agent, specializing in luxury properties from Anna Maria Island to Siesta and Longboat Key.

But for Jim, it was never just about square footage, once again, Jim choose activism over profits.

Through his company, CNRG Florida, he envisions a non-profit partnership to convert empty storefronts in struggling neighborhoods into rent-free gallery spaces for local artists from those communities. He also is planning his next public art installation harnessing the oceans power to create a visual and auditory experience.

Artistic Expression

Jim’s return to art wasn’t just a creative impulse—it was a continuation of everything he had lived and fought for. His work is bold, symbolic, and unapologetically political. It speaks in red—the color of rage, remembrance, urgency, and blood.

He’s become known for his massive outdoor installations, often wrapping or transforming public spaces into living testaments of resistance, healing, and identity. Through these works, he channels not just his own journey as a man living with HIV, but the broader fight for dignity, awareness, and visibility.

“Art lets me say what words can’t,” he says. “It reaches people before they know they’re listening.”

Jim doesn’t just create. He disrupts. He illuminates. He speaks the unspeakable in ways that make people stop and feel. His art isn’t just seen—it’s felt.

Personal Life

Since 1993, Jim has shared his life with Alain Sopena-Destresse, a quiet soul from Béziers, France, who once barely spoke English and now shares a language made of laughter, loyalty, and decades of memories.

Together, they’ve built a life that stretches from the wild streets of San Francisco to the calm shores of Florida’s east coast—from the Castro to Biscayne Bay. Along the way, there have been dogs and cats, road trips and protests, heartbreaks and healing, and a love that’s stood the test of time, change, and everything in between.

30+ years later, they’re still side by side—partners, survivors, and soulmates.

Closing Note

Jim Buresch’s life has been many things: loud, quiet, messy, brave, scandalous, sacred. But above all, it’s been wide open—lived at full volume, with purpose, grit, and grace.

He’s not done yet.